Key Benefits of Physiotherapy

- Restores Hip Stability & ControlPhysiotherapy aims to restore neuromuscular control and kinesthetic awareness in the hip joint. This includes addressing impairments like aberrant lumbo-pelvic movement and poor control with functional testing. By strengthening the core and kinetic chain, and targeting muscle activation patterns, physiotherapy helps to increase muscular stability and compensate for altered sensory input that can occur with articular damage. It directly addresses hip instability and poor neuromuscular control, which are hypothesized to replicate or exacerbate the injury mechanism.

- Corrects Compensatory Movement PatternsPhysiotherapy focuses on correcting aberrant hip kinesthetics and movement dysfunctions. This includes addressing issues such as muscular imbalance, joint contracture, and deconditioning. It also targets compensatory responses like lumbar hyperlordosis, low pelvic tilt, and high sacral slope, which can create functional impingement by altering acetabular rotation relative to the femoral head. Physiotherapy can target areas likely overloaded in FAIS as part of a compensatory response for loss of motion at the hip joint, including the lumbar spine, surrounding hip and core musculature, sacroiliac joint, and pubic symphysis.

- Non-Surgical Management OptionConservative management, which often includes physical therapy, is increasingly recommended and has shown successful outcomes in patients deemed surgical candidates. Clinically important improvements in self-reported outcome measures (such as the International Hip Outcome Tool – 33, Numeric Pain Rating Scale, Patient Specific Functional Scale, and Global Rating of Change) have been observed. In some case series, patients who completed conservative management elected to forego surgical management. Research indicates that nonsurgical treatment can produce measurable improvements in pain and function among athletes, including their ability to participate in sports activities. This method is considered less invasive, less expensive, and less prone to complications than surgical alternatives. It is suggested that physical therapy could be considered earlier in the treatment plan, as its median cost is significantly less than typical diagnostic costs and estimated definitive FAIS management costs.

- Pre/Post-Surgical OptimizationPhysical therapy can serve as effective pre-habilitation before an arthroscopic procedure if pain and functional limitations persist. Furthermore, if surgical interventions are pursued, it is critical that neuromuscular control dysfunction is addressed and movement patterns are corrected through rehabilitation, otherwise symptoms may become persistent and recurrent even after surgery.

Evidence-Based Physio Approaches

Physiotherapy interventions are typically individualized based on the patient's unique needs, impairments, and tissue irritability.

- Motor Control Training: Treatment focuses on restoring normal kinesthetic awareness to the joint and improving muscle activation patterns. This includes progression to dynamic control and functional movements, as well as proprioceptive/kinesthetic training. Physiotherapy often involves posture and gait training and core and kinetic chain strengthening and coordination.

- Progressive Strengthening: Exercise selection progresses from isometric to eccentric then concentric muscle-specific contractions when pain-free, potentially advancing to power and plyometric exercises. Strength assessment might involve a hand-held dynamometer.

- Manual Therapy: When predominant joint mobility restrictions are identified, techniques such as joint mobilization (including self-mobilizations) are utilized. Low-grade mobilizations (I or II) are used for pain reduction in subjects with higher tissue irritability, while high-grade mobilizations (III-V) are implemented to improve full pain-free range of motion (ROM) in those with lower tissue irritability. If soft tissue is the primary barrier to movement, interventions may include hands-on and instrument-assisted soft tissue mobilizations, complemented by contract-relax stretching.

- Gait Retraining: Phase 1 of physical therapy protocols may emphasize gait and pelvic alignment. Physiotherapy for FAIS and labral injury specifically involves gait training.

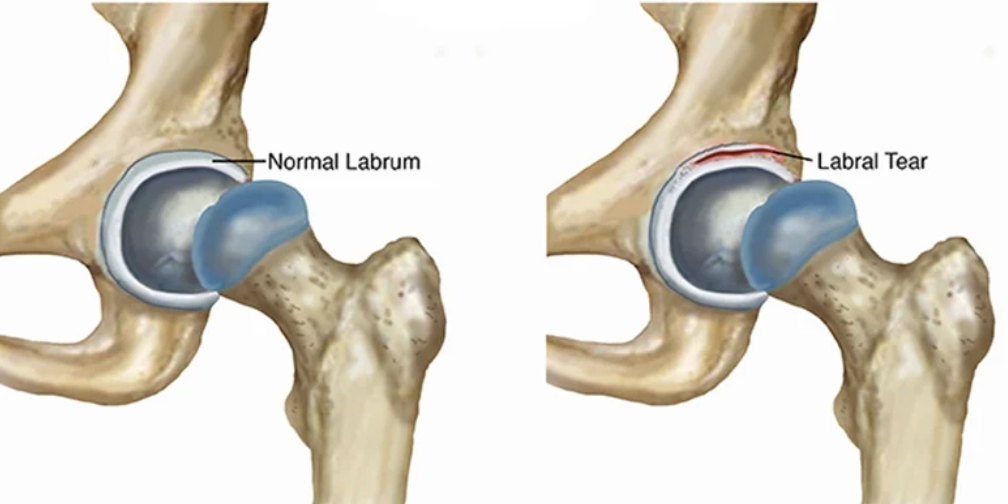

Prognosis: Can a Labral Tear Heal Without Surgery?

While a hip labral tear itself has limited inherent healing potential, conservative management can often lead to significant symptomatic relief and functional improvement, frequently allowing patients to avoid surgery.

- Conservative Treatment Success Rates:

- Conservative management produces measurable improvements in pain and function in athletes.

- In one study, all surgical candidates who completed conservative management elected to forgo surgery at a two-year follow-up, showing clinically important improvements in self-reported outcomes.

- Another study found significant improvement in all four functional outcome measures over a minimum of one year of nonsurgical treatment, with 71.2% of patients satisfied.

- Best candidates for non-surgical management are likely those with minimal femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) who are willing to alter their lifestyle and accept occasional discomfort. Treatment plans should always be decided on a case-by-case basis.

- Key Factors Affecting Outcomes:

- Individualized treatment is crucial, addressing neuromuscular control and mobility deficits. Physical therapy often involves posture and gait training, and core and kinetic chain strengthening and coordination.

- Activity modification is advised to limit stress on the hip, such as avoiding deep squats, deadlifts, lunges, and distance running.

- Treatment vigor is adjusted based on tissue irritability and pain level.

- When Surgery May Be Needed:

- Despite functional improvements, many patients undergoing conservative care still report persistent pain (48.1%), activity limitations (69.2%), and a continued interest in surgery (40.4%).

- Surgery may be considered for patients who fail conservative treatment measures and are deemed appropriate surgical candidates.

- While not explicitly stated as a direct indication over conservative care in these sources, clinical practice often considers surgery for persistent mechanical symptoms (e.g., locking, catching) that limit daily life.

- Patients with more pronounced radiographic signs of FAI may be treated more aggressively surgically due to concerns about accelerated cartilage damage and progression to osteoarthritis.

- Typical Recovery Timeline (Conservative Management):

- A physical therapy trial for a minimum of 4 to 6 weeks is frequently efficacious.

- Conservative management can last, on average, around 81 days (about 2.5 months), with patients improving over approximately 8.6 visits.

- Rehabilitation often follows a 3-phase template: pain control and gentle mobility (0-2 weeks), progressive loading and functional activities (2-12 weeks), and sport-specific drills leading to return to full activity (12-24 weeks/up to 6 months if symptoms resolve).

Physiotherapy Treatment Plan

- Phase 1: Biomechanical Assessment (Weeks 1-2): This initial phase is crucial for classifying the patient based on their neuromuscular control and mobility impairments, with the assessment's intensity guided by tissue irritability. Key evaluations include hip ROM (focusing on internal rotation and flexion), strength testing (e.g., glute medius, deep rotators), functional screens (e.g., single-leg squat, step-down), gait analysis, and special provocation tests like the FADIR test.

- Phase 2: Acute Management (Weeks 2-6): The primary goal here is to restore pain-free active ROM, followed by full passive ROM, while prioritizing pain management.

- Strengthening: Starts with isometric exercises and progresses to low-load dynamic movements such as clamshells (progressing to banded) and quadruped hip extensions.

- Mobility: Involves capsular stretches and soft tissue techniques like foam rolling for the TFL and hip flexors (while avoiding direct labral compression).

- Activity Modification: Patients are advised to limit activities that place significant stress on the joint or involve extreme hip motion. This includes avoiding deep squats, prolonged sitting (by taking standing breaks), impact activities (like running/jumping), deadlifts, and lunges.

- Phase 3: Progressive Loading (Weeks 6-12): This phase advances to dynamic control and functional movements as symptoms permit.

- Advanced Strengthening: Focuses on eccentric control (e.g., 3-second step-downs, Nordic hamstring slides) and rotational stability (e.g., banded monster walks, Pallof press with hip hinge).

- Functional Integration: Progresses through squat variations (e.g., box squats to tempo goblet squats) and single-leg balance exercises, including plyo box touch-downs.

- Phase 4: Sport-Specific Preparation (Weeks 12+): The aim is to restore the patient's ability to participate in sports. This involves agility drills (e.g., lateral shuffles with band resistance), pivot training (gradually reintroducing rotational loads), and power development (e.g., medicine ball rotational throws). For athletes, sport-specific biomechanical evaluation and correction are paramount for successful management, especially in sports demanding extreme hip flexion, internal rotation, and adduction like dance and hockey.

Manual Therapy Interventions: These are an integral part of conservative management, used to improve pain-free soft tissue and joint mobility.

- Joint Mobilization: Utilized for identified joint mobility restrictions, with low-grade mobilizations (I or II) for pain reduction in higher irritability cases, and high-grade (III-V) mobilizations for improving full pain-free ROM in those with lower tissue irritability.

- Soft Tissue Techniques: Include hands-on and instrument-assisted soft tissue mobilizations, complemented by contract-relax stretching, to enhance pain-free soft tissue mobility.

Prevention Strategies

- Implement Targeted Physical Strategies: Drawing from successful conservative management approaches, prevention involves:

- Activity Modification: Limit activities that place significant stress on the hip or push it to extreme ranges of motion where impingement and labral tears are thought to occur. This includes avoiding deep squats, deadlifts, lunges, and distance running.

- Targeted Strength and Neuromuscular Control Training:

- Address muscular imbalance and deconditioning.

- Focus on core and kinetic chain strengthening and coordination. This includes strengthening hip stabilizers like the gluteus medius and deep rotators, which are often impaired in individuals with FAIS and labral tears.

- Improve kinesthetic awareness and dynamic control to prevent aberrant lumbopelvic movement.

- Progress through functional activities to build tissue resilience, potentially including controlled eccentric loading.

- Movement Preparation & Mobility:

- Restore and maintain adequate hip mobility and address tissue extensibility. This involves promoting pain-free active range of motion (AROM) and full passive range of motion (PROM).

- Utilize dynamic warm-ups and soft tissue mobilization techniques.

- Biomechanical Optimization:

- Avoid end-range hip flexion in weighted exercises to prevent impingement.

- For hypermobile individuals, focus on isometric holds in neutral positions to build stability and control [Outside Source Information: This is a common physical therapy strategy for hypermobility, consistent with the source's emphasis on neuromuscular control for individuals with excessive joint mobility, but not explicitly stated].

- Sport-Specific Adjustments: For athletes, especially in sports demanding extreme hip flexion, internal rotation, and adduction (e.g., dance, hockey), a detailed movement analysis and correction is paramount. This may involve modifying techniques like the hockey "butterfly technique" implicated in labral tear development.

- Early Consideration of Physical Therapy: Physical therapy, particularly a dedicated and individualized program, is frequently efficacious and has limited downside. It could be considered earlier in the treatment plan, even before extensive diagnostic measures.

FAQs

1. "Can my hip labral tear heal on its own?"

- Complete natural healing is unlikely due to the labrum's limited blood supply.

- However, significant improvement is possible through non-surgical management, which is widely recommended as a first-line approach.

- Non-surgical treatment typically includes:

- Specialized Physical Therapy: This addresses individual impairments like mobility limitations, neuromuscular control deficits, and strength weaknesses. The goal is to restore pain-free active range of motion and progress dynamic control.

- Activity Modification: Limiting activities that place significant stress through the joint or involve extreme hip motion.

- Inflammation Management: Such as NSAIDs and intra-articular corticosteroid injections. However, intra-articular injections are considered to have limited therapeutic benefit in isolation and are not long-term solutions.

- Many patients can successfully avoid surgery: One study found that 65% of patients avoided surgery with physical therapy, and a case series reported that all six subjects, initially surgical candidates, elected to forego surgery after satisfactory completion of conservative management over a two-year follow-up period. Another study noted 44% of patients with pre-arthritic intra-articular hip pain did not require surgery after physical therapy.

2. "Is running safe with a labral tear?"

- The safety of running is dictated by your symptoms and the development of hip stability.

- Stop Immediately If: You experience pinching pain during your stride or increased stiffness after running. Activities that cause significant stress or involve extreme hip motion should be limited.

- You May Continue If: You are pain-free during single-leg hops and have completed a period of hip stabilization training. Physical therapy protocols aim to restore dynamic control and functional movements, with symmetrical functional tests without symptom reproduction indicating readiness for higher-level activities.

3. "Will I eventually need surgery?"

- A trial of 6 months of quality physical therapy is strongly recommended as a first step. Patients can experience significant functional improvement with non-surgical management. Studies support physical therapy as a successful first approach for managing symptoms and potentially preventing the progression of intra-articular joint disease.

- Surgery is typically considered if:

- Persistent pain despite dedicated rehabilitation: Even with functional improvements, a significant portion of patients (48.1% in one study) report no improvement in their pain and 40.4% may still consider surgery. Unresolved pain is a primary reason for surgical consideration.

- Femoroacetabular Impingement (FAI) is causing repeated damage: FAI is a movement disorder resulting in aberrant contact that is highly associated with labral tears (up to 95% of FAI patients have an associated tear). Correcting abnormal bony morphology (cam or pincer lesions) through surgery is crucial to protect the labrum from reinjury and prevent early osteoarthritis.

- Significant tear causing joint instability: The labrum is vital for hip stability through its suction effect. If the labral tissue is damaged beyond repair, ossified, deficient, or incompetent, reconstruction may be necessary to restore the labral seal and stability to the hip joint.

4. "Can I keep weightlifting?"

- Modified strength training is crucial. Activities that place significant stress through the joint or put the hip at the extremes of motion (e.g., adduction, internal rotation, and flexion) should be limited.

- ✅ Safe Options:

- While specific exercises like trap bar deadlifts, landmine squats, and isometric holds are not explicitly named in the sources, physical therapy protocols emphasize progressing from pain-free isometric contractions to eccentric and then concentric exercises to build strength and control. Exercise selection is individualized based on the patient's ability to perform tasks without provoking lasting symptoms.

- ❌ Temporarily Avoid:

- Activities like deep squats (below parallel), heavy hip thrusts, and Olympic lifts often involve deep hip flexion and high loads that are commonly associated with impingement and labral tears. These activities are generally advised to be limited to avoid increasing tissue strain and symptom aggravation.

- Pro Tip: The physical therapy progression includes eccentric muscle contractions to build control and strength, with the intensity guided by tissue irritability.

Our Specialized Approach to Rehab

- Evidence-Based Expertise

- Protocols grounded in the latest research for hip preservation

- Specialized training in FAI and hip joint rehabilitation

- Experience with athletes, active adults, and chronic cases

- Personalized Care

- Analysis of your movement patterns and structural factors

- Tailored plans for your goals (e.g., return to sports, pain-free daily living)

- Ongoing adjustments based on your progress

- Holistic Recovery Support

- Education on activity modification and joint protection

- Guidance on safe return to running, jumping, or weightlifting

- Long-term strategies to prevent recurrence

Take the First Step Toward Pain-Free Movement

Don’t let hip pain sideline you from the activities you love. Our team will help you regain stability and confidence in your hips.

Book Your Specialized Assessment Today:

Serving Thornhill, Langstaff, Newtonbrook, Willowdale, North York, Markham, Richmond Hill, Concord, and North Toronto.

Convenient Thornhill location with evening and weekend availability.