Pain or dysfunction involving the elbow joint.

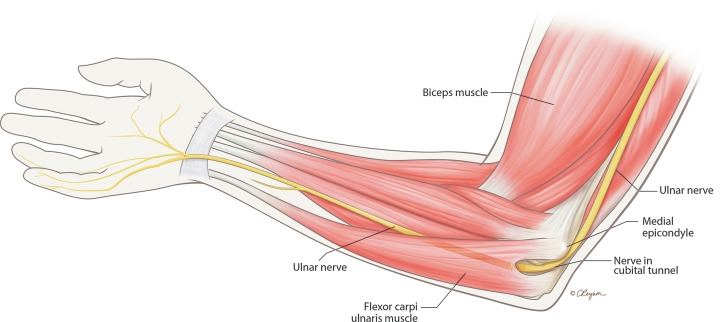

Definition:Medial epicondylitis (ME), commonly known as “golfer’s elbow,” is an overuse syndrome of the elbow. It specifically involves injury to the flexor-pronator group (FPG) of muscles, which is also referred to as the common flexor tendon (CFT). This injury occurs where the FPG attaches to the medial epicondyle of the humerus.

The primary mechanism of injury is repeated eccentric loading of the FPG muscles. This often happens during activities that combine wrist flexion and forearm pronation with a valgus force on the elbow, such as those performed by overhead throwing athletes or manual laborers. Repeated stress leads to microtrauma and degeneration of the musculotendinous units. While the suffix "-itis" implies inflammation, it is primarily applicable to the acute phase of the condition. In chronic cases, degenerative changes predominate (tendinosis), characterized by calcification, fibrosis, vascular proliferation, and hyaline degeneration without significant inflammatory infiltration. Despite its common name, ME is relatively uncommon in golfers and is four times less common than lateral epicondylitis (LE).

Differential Diagnosis:It is crucial to consider several other pathologies that can cause medial elbow pain:

Medial epicondylitis involves injury to the flexor-pronator group (FPG) of muscles, also referred to as the common flexor tendon (CFT), at their attachment to the medial epicondyle.

The primary mechanism of injury for medial epicondylitis is repeated eccentric loading of the flexor-pronator group of muscles. This repeated stress leads to microtrauma and degeneration of the musculotendinous units.

Several factors can increase an individual's risk of developing medial epicondylitis:

A comprehensive physiotherapy treatment plan for Medial Epicondylitis (Golfer's Elbow) typically progresses through distinct phases, focusing on pain relief, rehabilitation, and a gradual return to activity. Conservative management is the primary approach, with up to 85–95% of patients responding to initial treatment. Surgical intervention is generally reserved for patients whose symptoms persist despite 3–12 months of conservative management.

The initial focus is on alleviating acute medial-sided elbow pain.

Once acute symptoms are alleviated, the rehabilitation focus shifts to stretching and strengthening the flexor-pronator mass. The initial goal is to achieve a full, painless range of motion (ROM).

The provided sources generally recommend soft tissue mobilization and joint mobilizations for musculoskeletal conditions like epicondylitis. However, the sources do not provide specific details on manual therapy techniques such as soft tissue massage to forearm muscles or joint mobilizations for elbow stiffness directly for medial epicondylitis, though they are common components of physical therapy for tendinopathies.

Reconditioning the upper limb to maintain tendon excursion and strength during rigorous stress is essential to prevent undue stress on the elbow and recurrence of symptoms.

Recover faster, move better, and feel stronger with expert physiotherapy. Our team is here to guide you every step of the way.

The recovery timeline for Medial Epicondylitis (Golfer's Elbow) can vary depending on whether the condition is managed conservatively or requires surgical intervention. Most patients, up to 85–95%, respond to initial conservative treatment.

Preventing medial epicondylitis focuses on reconditioning the upper limb, optimizing activity mechanics, and making appropriate equipment adjustments to reduce stress on the elbow.

Q: Can I still workout with golfer’s elbow?

A: While you should avoid activities that instigate or exacerbate your medial elbow pain, especially those requiring repetitive wrist flexion, forearm pronation, and valgus stress on the elbow, you can generally continue to work out by modifying your routine. Pain typically improves with rest from aggravating activities. Activities like grasping or pulling can reproduce pain. Patients often experience pain exacerbated by daily activities, particularly bothersome during the late cocking or early acceleration phases of throwing or golfing. Resisted wrist flexion, forearm pronation, or forceful grip may be weakened and can exacerbate elbow pain.

Instead of focusing on aggravating upper body movements, you should prioritize strengthening of the shoulder girdle and scapular stabilization, which is crucial for all patients, especially throwers. Additionally, core and lower body strengthening can be very beneficial, as they can improve overall mechanics and support activities involving moderate to heavy resistance without directly stressing the elbow. The goal is to recondition the upper limb to maintain tendon excursion and strength, preventing undue stress and recurrence of symptoms.

Q: When is surgery needed?

A: Surgery for Medial Epicondylitis (Golfer's Elbow) is generally rare, as up to 85–95% of patients respond to initial conservative management. Operative interventions are typically reserved for patients with recalcitrant or recurrent symptoms who do not respond despite an aggressive regimen of nonsurgical therapy. The duration of conservative management before considering surgery varies but is commonly cited as 3 to 12 months. Some sources specify a period of 4 to 6 months.

The main exception to this guideline is the elite athlete with definitive tendon disruption that is clearly visible on MRI. For these specific cases, surgical repair of the tendon may be considered earlier, as it could allow for a quicker return to pre-injury performance levels compared to prolonged nonsurgical treatment. Following surgical intervention, patients typically return to full, unrestricted activity within 3 to 4 months post-operatively. Overall, 97% of patients return to pre-operative activities after surgery.

Our certified physiotherapists specialize in:

✅ Biomechanical assessments (elbow, wrist, shoulder)

✅ Custom eccentric loading programs

✅ Electrical stimulation for chronic cases

✅ Sport-specific rehab for golfers, tennis players, and laborers

Serving Thornhill, Vaughan, Markham & North York

📍 398 Steeles Ave W #201, Thornhill, ON

📞 (905) 669-1221

🌐 *Book Online*

Don’t let elbow pain sideline you—start your rehab plan now for a stronger, pain-free grip.

🔹 Call or Book Online for an Assessment!

Explore the latest articles written by our clinicians